Natural heritage site.

Details of Site Location: At the original shoreline and the creek as boundary between the cities of Toronto and Mississauga.

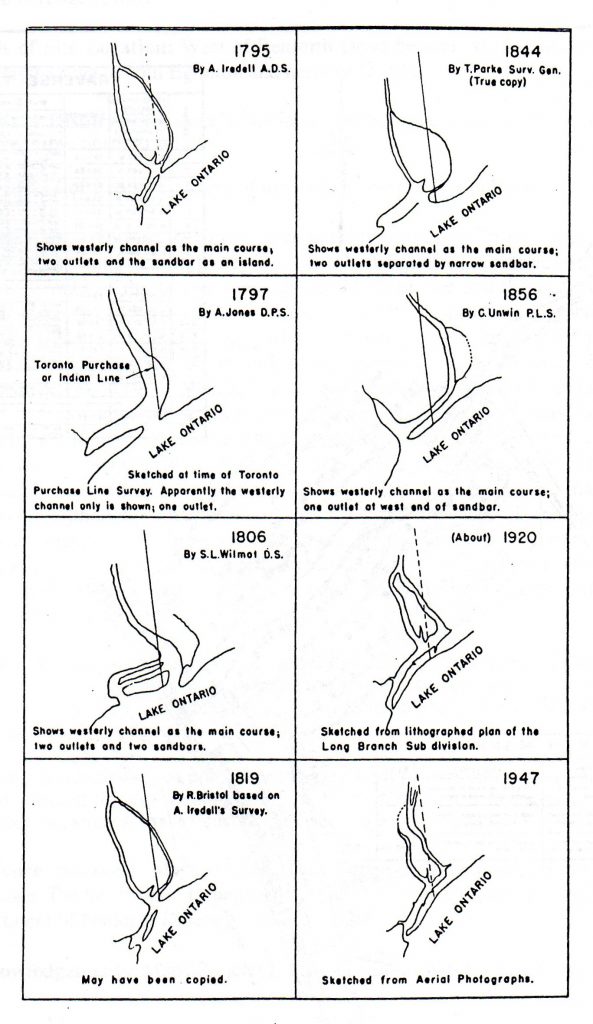

Boundary History: The boundaries, best explained by the attached map, have been altered completely.

Current Use of Property: Marie Curtis Park.

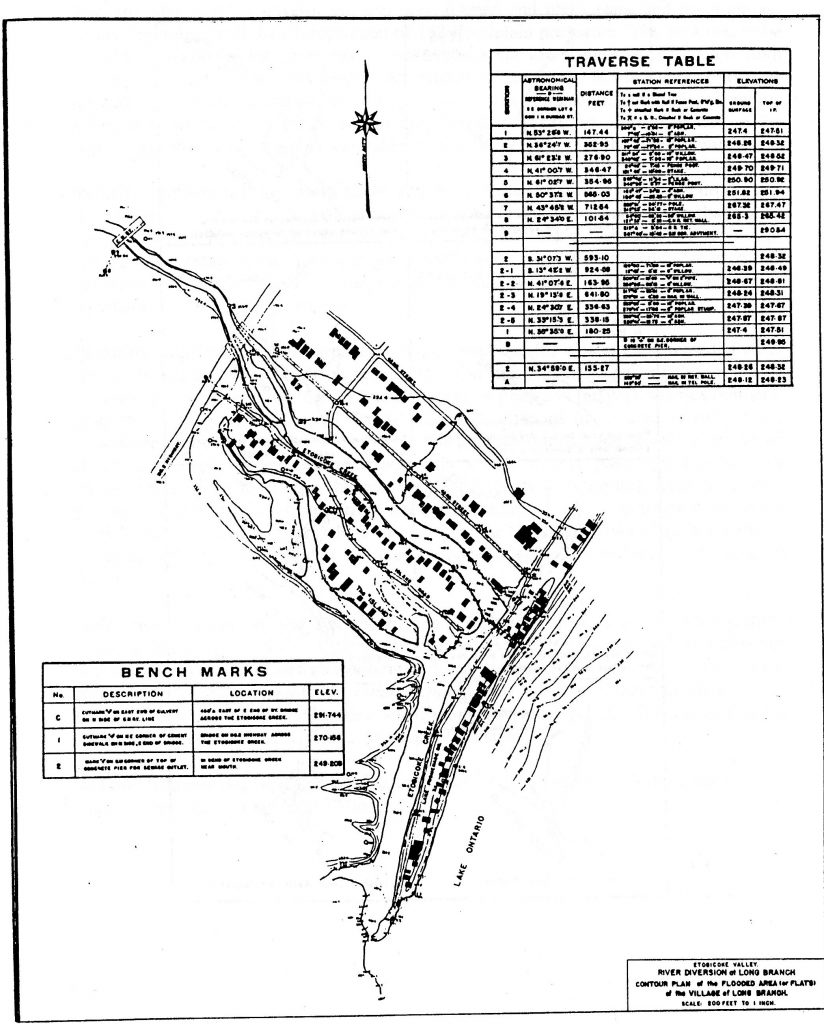

Historical Description: Etobicoke Creek is a large system with many tributaries, draining an area of 205 square kilometres. About one quarter of the creek’s system is within the city boundaries. Historically, the mouth of the creek was known as one of the finest wetlands and wildlife habitats along the Lake Ontario shoreline. An outstanding feature was the once enormous flocks of passenger pigeons that darkened the skies. Surrounding the creek’s mouth and lower course were Carolinian forests of white pine and oak. At the mouth was an island, flanked on the west side by sandy flats and dunes, and a gradually growing peninsula. Annual spring floods enriched the lands around the mouth with nutrients. The marshes provided fish spawning grounds, and the creek was famous at one time for the salmon runs upriver. Aboriginal peoples grew corn on the fertile flatlands at the mouth, and later introduced squash and beans. When Colonel Samuel Bois Smith of the Queen’s Rangers was granted 1,530 acres in 1799 – a body of land known to history as the Smith Tract – he left the mouth of the creek as he found it and built only his house there. But he allowed timbering of his lands, as did others, and by 1842 half of the great forests of Etobicoke Township had been cut down. As a result, serious flooding problems began about 1850. Although the mouth of the creek did not have good anchorage, some shipping was done from there, and Colonel Smith built the ship Defiance there from his own oak forest in 1835. The Mississauga Indians, from whom the land had been taken, were guaranteed perpetual fishing rights in the river, but were driven out by commercial fishermen and advancing settlement. In 1871, Colonel Smith sold 500 acres to James Eastwood, and within a few years the forest cover was gone and the creek flats were covered with shacks and shanties. Then Eastwood sold 75 acres of waterfront land to a syndicate for development in 1883, and the next year a plan of subdivision was registered as Long Branch Park with 219 cottage lots. Ten years later, the radial line was bringing more people into the area, and factories were being built. The passenger pigeon was extinct by 1902. Colonel Smith’s house survived until 1955. The Long Branch lands south of the Lake Shore Road were subdivided by the Eastwood family in 1920 and developed as Long Branch. Between the two World Wars, the community of Alderwood developed. Industrial and residential areas filled up. The Queen Elizabeth Way and the Gardiner Expressway were built. Lands unsuitable in their natural state for development were filled in and creeks and streams buried, with few remaining by 1900. Groundwaters became polluted. Waters flowing into the system from Brampton and Mississauga were contaminated, the worst being from Spring Creek, which ran through the airport lands. Etobicoke Creek became the most contaminated system in the region, with higher concentrations of PCBs than elsewhere. Fish and wildlife were either reduced or vanished. Reports and studies over the years consistently recommended remediation and removal of the weir installed on the creek by the Toronto Golf Club, because it blocked fish movement. The first engineered alteration of the lower creek began in 1929, when the beach sandbar across the mouth of the river was reinforced by cribwork to allow for the extension of the Lake Promenade. Severe flooding and property damage occurred in 1948 because of this additional block to the outlet. In 1952, more flooding destroyed the houses on the sand flats and sandbar. In response, Long Branch Council acquired 27 lakefront lots and began to plan for flood control. It had become inescapable that the channelling done in 1949, taking the creek through the sandbar, was woefully inadequate. Before the planning was complete and any work actually begun, in 1954 Hurricane Hazel caused seven deaths, destroyed 56 more houses, and left 365 people homeless. By this date, the Metropolitan government had been formed and plans were laid for improvements beginning with the expropriation of 183 floodplain properties. The area was to be raised by landfill, the flats converted to parkland, and the lower creek re-channelled. Both the degree of alterations and costs were enormous. In 1959, Marie Curtis Park was opened. By this date, there was not a single trace of the original creek mouth remaining, although some remnants of the surrounding forest may still be seen upstream on the adjoining lands. In 1990, a plan was made for the “naturalizing” of the creek mouth.

Relative Importance: Etobicoke Creek and its mouth are unquestionably important, and the history of change introduced there is a textbook illustration of the damage that can be done by human interference. Not only is the creek a boundary between two townships and now two cities, it has been a major wildlife habitat and scenic beauty location that has been almost polluted and engineered out of existence and should be used as a guide on what not to do to a watercourse.

Planning Implications: It is strongly recommended that the cleanup and remediation of the water and adjoining lands be accelerated, and that “naturalizing”’ of the mouth be undertaken by nature rather than by human beings. A plaque in the park should commemorate the 1799 grant to Colonel Smith and the location of his house, as well as the agriculture and culture of the First Nations inhabitants. The plaque should give special attention to the vanished wildlife, especially to the extinct passenger pigeon. The “naturalizing” plan to restore the vanished sand dunes is intriguing from a heritage perspective, but should not be carried out unless nature dictates a willingness to do the work. And it should be nature alone that restores the flora and fauna along the route of the river, although nature might be aided by planting some descendants of the original forest.

Reference Sources: Wayne Reeves, Regional Heritage Features on the Metropolitan Toronto Waterfront (1992); Citizens Concerned About the Future of the Etobicoke Waterfront and Environmental Planning and Policy Associates, Toward the Ecological Restoration of South Etobicoke Final Report (1997); map, “Reconnaissance of the Country between the rivers Humber and Etobicoke from the Lake Ontario to Dundas Street on the North” (1867), Public Archives of Canada.

Acknowledgements: New Toronto Historical Society; Toronto Field Naturalists; Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation. [4/22/2020 Note: The Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation changed their name to the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation on January 8, 2019]

The changing configuration of the Etobicoke Creek mouth, 1795-1947. (Ontario Department of Planning and Development, Etobicoke Valley Conservation Report)

Residential development on the Etobicoke Creek Flats, 1947. Preparations were then being made for cutting a diversion channel through the Lake Promenade sandbar. Island Road lies between two river channels. (Ontario Department of Planning and Development, Etobicoke Valley Conservation Report)